Land Arts in the Limestone Coast (Part 2): November Retreat

This is the second post in the Land Arts in the Limestone Coast series, centred on the 10-day November retreat in the Limestone Coast that I and other artists from around Australia and abroad took part in.

Following my residency, which I wrote about in the previous post, I returned to the South East between 1 to 11 November to take part in the Land Arts Retreat. The brainchild of Professor Ross Gibson (from the University of Canberra) and sensitively prepared by curator Nick Keys, the Retreat was an opportunity is for 10 artists from across Australia and beyond, visiting key sites that tell the story of the region as a changescape and focussing on landscape history and the exploration of land use. TheIn the second phase in October/November 2020, participants are invited to return to the Limestone Coast to present aesthetic responses to the field retreat.

Artists were selected based on their enthusiasm for field experience, their sensitivity to regional engagement and site-specificity, their curiosity about landscape history and cultural practices (old and new), their willingness to expand the frame of art to include all human intervention in the landscape, and their previous track record in working in this way. As the youngest artist in the group, I was privileged to be surrounded by an inspiring array of professional artists, including interdisciplinary artist Simryn Gill (NSW/Malaysia), ephemeral environmental artist Elaine Clocherty (SA), choreographer and BodyWeather specialist Tess De Quincey (NSW), multidisciplinary artist Fiona Kemp (NSW), assemblage artist Janine MacKintosh (SA), digital media artist Grayson Cooke, visual artist Jude Roberts, land artist Ted Carey (Texas, US), local Limestone Coast artist Trudy Tandberg, movement artist (and fellow Theatre Resident Artist) Cynthia Schwertsik and Country Arts’ Merilyn De Nys, alongside Ross and Nick.

After arriving on Friday 1 Nov and meeting one another over dinner at Mt Gambier restaurant Belgiornio’s, our Retreat started in earnest the next day, learning of the local First Nation Boandik perspectives of place. Our morning began with a Welcome to Country by Boandik Elder Aunty Michelle Jacquelin-Furr in the city’s central Cave Gardens, who donned a remarkable possum cloak in which a detailed account of Boandik history was burnt, amongst them the Craitbul story, which represents an extensive oral history of volcanic activities and coastline variation in the area. Our conversation continued in the Riddoch Gallery over a large scale map of the Limestone Coast (third image below), pieced together by Nick from earlier survey map and acting as a document to which we could annotate our experiences.

1) Welcome To Country in the Mt Gambier Cave Gardens

2) Aunty Michelle's possum cloak

3) Group discussion over the Limestone Coast map

We departed for lunch at Pt MacDonnell (the southern-most town in South Australia), where we met Boandik Elder Ken Jones. Ken’s business, Bush Repair, specialises in bush hut repair, field surveys, landscape revegetation and maintenance, and Boandik cultural tours. Port MacDonnell offered a diverse pocket of encounters, included the remnants of a petrified forest off the coastline, Boandik middens (where seafood was collected), native plants used for food and medicinal purposes, and a journey through the coastal sand dunes, where Ken led us in meditation and taught us a local whale song. In spite of this, and as would become ever more juxtaposed as the Retreat continued, the modern world encroached: on our journey along the beach back to the cars, a motorbike roared past us on the sand, tearing away through the retreat dunes. In the late afternoon, our group finally visited Mt Shank, taking in the Crater Rim views of the surrounding area as I had during my Residency some weeks earlier.

1) Remnants of the petrified forest off Pt MacDonnell

2) Simryn Gill and Ken Jones in conversation next to a midden

3) Ken leads us through the coastal dunes

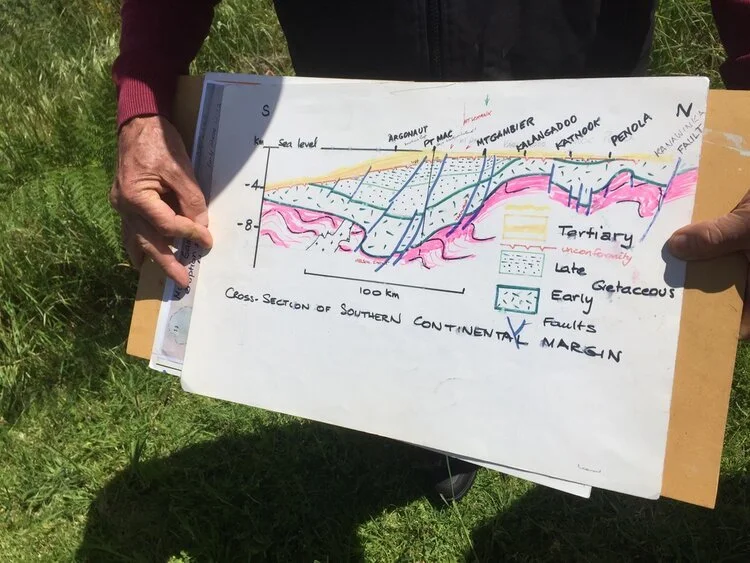

The following day, Sunday 3 November, we were joined by geologist Robert ‘Bob’ Dalgarno, who educated us on the many varied geological forces shaping the land.

As we learned, there are a number of geological processes operating at immense timespans that have forged the Limestone Coast. At the largest time scale, the coast was initially formed through the rift of Gondwana into the continents Antarctica and Australia, drifting gradually apart to form the Southern Ocean. With fluctuations in sea levels on the coast over many millennia, successive deposits of skeletal fragments from marine organism leave layers of calcium carbonate, successively building to result in reefs of limestone. In the past million years, this sea-level fluctuation has resulted constant shift of the coastline, introducing sand dune systems that have become the modern-day ranges in the Limestone Coast (including the Wattle Range and Bakers Range), as well as significant changes in the water table levels which have dissolved the limestone to result in the regions impressive cave systems and sinkholes. In the past 10,000 years, fault lines left by the continental rift created fissures in the earth’s crust, culminating in volcanic activity forming sites including Berrin/Mt Gambier, Waawor/ the Blue Lake and Mt Schank through to Central Victoria.

Our first port of call was the Umpherston Sinkhole, an exemplar of the process of Limestone dissolution and cave roof collapse. Later, we visited various cuttings demonstrating geological strata throughout the city, and later the volcanic sites of the Blue Lake, Leg of Mutton Lake, Valley Lake and Browns Lake.

1) Our group in the Umpherston Sinkhole

2) Bob points out details of the sedimentary layers next to the local Salvation Army (ironic!)

3) Bob's cross-section diagram of the Limestone Coast's geography

In the afternoon, we descended to the Blue Lake’s Pump Station, where we were met by Jeff Lawson, whom Nick referred to as the region’s water guru. Jeff’s Master’s degree investigated water activity in the Blue Lake and surrounding Limestone Coast region, and we collectively benefitted from his expertise, learning of the complex interactions of water use and in the region. A lengthy discussion took place on the impacts of centre-pivot irrigation and its impacts on confined and unconfined aquifers, as well as gas drilling in the area, wherein Jeff reasoned that although there are significant problems with shallow drilling, deep drilling below the water is relatively safe.

Towards the evening, we visited the Kilsby Sinkhole, a submerged cavern on the outskirts of Mount Gambier filled with crystal-clear water. Taken over by the army in the 1970s for covert dive training, it currently operates as a snorkelling and cave-diving tourist hotspot as well as the Sinkhole Gin distillery (using the sinkhole’s water in the recipe).

1) Pump machines in the Blue Lake Pump House

2) & 3) Our group in discussion with Jeff Lawson at the Blue Lake

4) The crystalline waters of the Kilsby Sinkhole

The next day, Monday 4 November, we departed Mount Gambier on an extensive road trip of the Limestone Coast. Our first stop was on the outskirts of Kalangadoo, where we met David New, the Aboriginal Engagement Officer for Natural Resources South East. A previous landholder, David invited Ngarrindjeri Elder Uncle Moogy (Major Sumner) to carve the first canoe (yuki) in the area in the past 100 years from a resplendent River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis). Later in the Retreat, we watch a documentary on the process of carving the yuki, which you can watch to the side here.

From Kalangadoo, we moved on to the Mt Burr range, where we visited a historic Boandik Rock Shelter, accompanied by both David and Mark Bachmann of Nature Glenelg Trust. There, we learned of the pre-settlement circumstances of the land - once likely an open valley hunting ground that would seasonally flood, now blanketed by a blackberry thicket and surrounded by thirsty exotic pine forests - as well as the massacres of Boandik people in the area, maintained in oral history if not documented.

1) & 2) The Scar Tree at Kalangadoo

3) A clearing in the Mt Burr Forest, now overrun with blackberry bramble and

4) A nearby Boandik rock shelter

From there, we continued to Mt Burr Swamp, a significant Nature Glenelg Trust swampland restoration project involving the block of drains on former pastoral land, thereby restoring the water table and allowing the remnant swamp to refill. As described on by NGT:

Mt Burr Swamp is providing a rare demonstration of what sustainable water management, threatened species recovery and large-scale native revegetation actually look like on the ground, while providing an opportunity for the community to actively participate in the exciting journey that lies ahead.

The site provides the opportunity to restore habitat for six nationally threatened species (as shown, in order): Little (formerly Dwarf) Galaxias (fish), Growling Grass Frog, Australasian Bittern, Southern Brown Bandicoot, Red-tailed Black Cockatoo and Southern Bent-wing Bat, as well as a range of other important or iconic species, such as the Brolga.

The biodiversity of the general area is best illustrated by the adjacent Marshes wetland reserve, known to support hundreds of species of native flora and fauna, including a host of significant species that will directly benefit from the restoration of the Mount Burr Swamp property.

As we further learned, the amazing restoration work of Nature Glenelg Trust continues further afield, at sites including Hutt Bay Wetland (SA), Eaglehawk Waterhole (SA), Long Point (VIC), Walker Swamp (VIC) and Kurrawonga (VIC).

In the late afternoon, we moved on to the Wirrianda Camp Ground at the Naracoorte Caves National Park for the night, where we went to the Bat Cave Conservation Centre at dusk to see the colony depart for their nightly feeding.

1) The main blocked drain at Mt Burr Swamp, which has retained water in the landscape

2) The Mt Burr Swamp

Our morning on Tuesday 5 November began with a tour of the Victoria Fossil Caves, a supplement for me of the same tour I took whilst on residency, but with another guide providing different perspectives. The Park’s website explains:

In 1969, two explorers squeezed through a gap in Victoria Fossil Cave and discovered a massive chamber full of fossilised remains.

For over 200,000 years this chamber had been a pitfall trap, storing the remains of thousands of animals. Layer upon layer of remains accumulated over the years, creating a rich fossil record of the ancient animals that roamed the area.Since then, this extraordinary fossil deposit has been a working paleontological dig – tens of thousands of fossil bones have been recovered. The fossils give us a unique window into the climate and environment of the times when these animals lived.

The Victoria Fossil Cave showcases the World Heritage features of the park. It is recognised the world over for its outstanding scientific value.

1) Our group in discussion with Rob England

2) The M Drain

3) An old river redgum, situated on the floor of an old swampland, now drained

4) Further drains in the Limestone Coast

Mid-morning, we departed for Bool Lagoon to meet Rob England and his mate Byron. Rob is a fifth-generation farmer in the area and something of a renegade. Disagreeing with the official verdict on the direction of water flow in the Limestone Coast (that it flows southwards, rather than north towards the Coorong), he conducted extensive independent research and authored the book ‘Cry of the Coorong’, which became a key document settling the dispute. As a previous member of the South East Water Conservation and Drainage Board, Rob’s intimate knowledge of the Limestone Coast’s drains revealed an complex mosaic of interactions between water and land as we toured various sites including the M Drain, several stopbanks in Baker’s Range (which at one point were blown apart by an aggrieved landholder, and traditional swampland areas indicated through the latent watercourses and depressions engraved in the land.

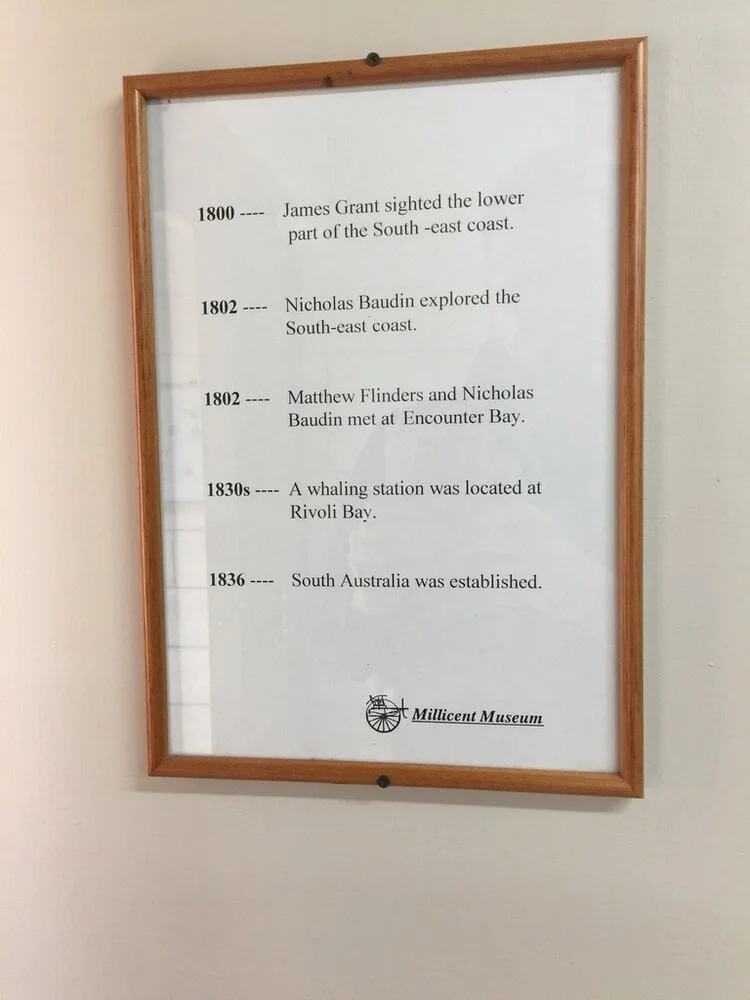

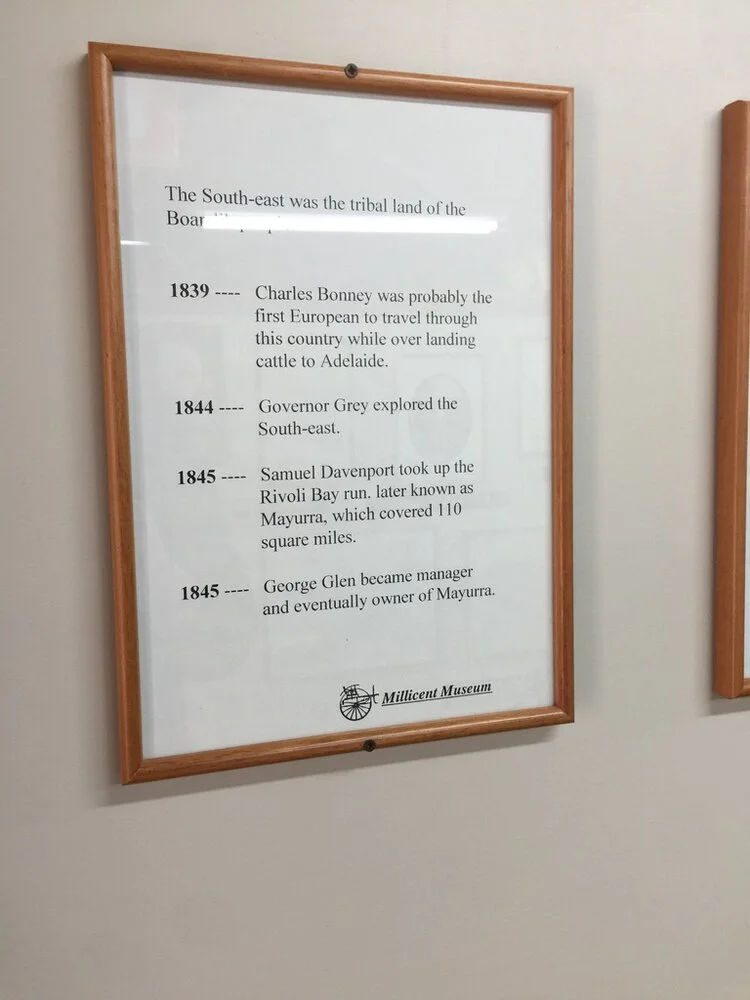

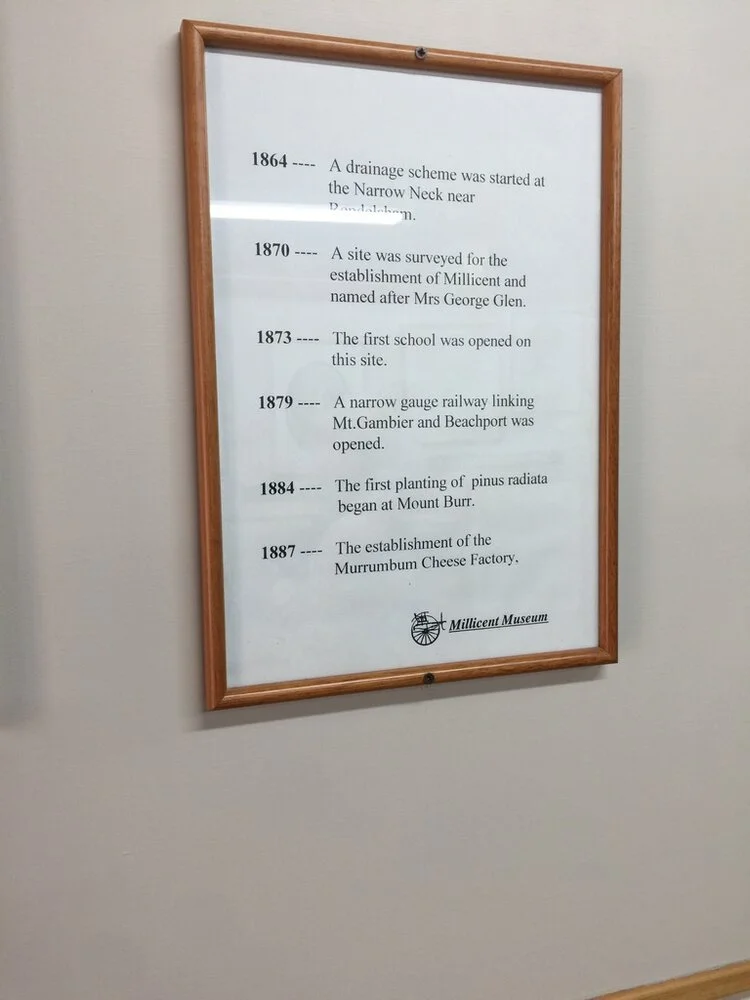

The following morning, Wednesday 6 November, we departed the Naracoorte Caves campground for Millicent. Exploration of the Millicent Museum gave a detail impression of early colonial life in the region through to present day, with the significance of drains made clear as a means of removing water from the landscape to make it arable and ‘productive’ (a desirable if not requisite trait of saleable land in the eyes of the colony’s government).

a colonial account of the Limestone Coast’s history

Following this, we went to visit the South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Board HQ in Millicent, meeting with members of the current board, including Lee Morgan, Brett McLaren and Pip Rasenberg. There we learned of the significance of Drainage Boards in the region’s history (many of these initially instigated in response to public drainage works by the State Government, later become district councils), and the ongoing role of the SE Drainage Board in management the now-over 5000km network of drains in the region. An extensive history of the Drainage system can be found at this site. As is evident, the Board has undergone a number of perspectival changes, from earlier colonialist attitudes of drainage in the service of land development (for transportation and agriculture, culminating in the impactful cuttings made in the 1950s) to an entity concerned with balancing multiple interests of primary production and conservation (a shift marked in the option of that word in their name in 1992).

Our meeting at the South East Drainage Board HQ in Millicent

After this meeting, we went on a tour with the Board of cuttings in the local area. First, we visited the Narrowneck, the first cutting made in the South East near Millicent. Lee noted that the Narrowneck was also a significant Aboriginal site, likely used to drive game through. This was followed by a visit to some of the drains from the 1950s drainage works, as well as drains outflow points at Beachport.

1) & 2) The Narrowneck

3) & 4) Drains installed in the 1950s

Lastly, we visited the Woakwine Cutting. I leave it to the Wattle Range Council website to explain:

“Said to be Australias biggest one-man engineering feat, the cutting was excavated to drain land behind the Woakwine Range, which is located approximately 12kms from Beachport. A parking bay and viewing platform is provided and the machines used to dig the cutting are on display. Free entry.

‘Woakwine’ is an Aboriginal name meaning ‘elbow or bent arm’ and refers to the shape of the large watercourse near the Woakwine Homestead. In fact, Woakwine is the only Aboriginal place name still used along the lower South East’s coastal region.

The McCourt family moved into the Woakwine area in the 1880s and soon realized that without richer land to compliment the rocky high country, living on the land would be difficult. As a result, in 1957, Mr. Murray McCourt decided to “have a go” at constructing a channel from the swamp through the range to Lake George in order to drain a large swamp on his property behind the Woakwine range.

The South Eastern Drainage Board assisted in designing and planning the proposed channel, however, these plans were not adopted as Murray believed the process was too costly.. Instead, Mr. McCourt decided to take a risk by having almost perpendicular walls. This type of development had never been seen in Australia before and there were obvious risks associated with the plans such as slipping of the steep walls. However, Murray, along with the assistance of one of his workman, Dick McIntyre, set out to prove that it could be done. Work commenced in May, 1957. Materials were carried from the cutting by the tractor drawn Carryall Scraper that scooped up the rubble and rocks once it had been loosened by a ripper. Other machinery also included a Caterpillar D7 crawler tractor complete with double drum winch and bulldozer blade.

1) The Woakwine Cutting

2) Our group in conversation with Michael McCourt

With a number in our group stunned at the immensity and audacity of the Cutting, a 4WD arrived in the nearby carpark. Its driver was Michael McCourt, Murray’s son. He spoke about what he saw as a positive impact on the land that the cutting had made for farming use, as well as his own practices of regenerative agriculture, which seeks to put carbon back into the topsoil through land management. Complex discussion ensued, with a variety of perspectives shared by the artists, Drainage Board members and landholders.

Our day ended at our new accommodation, Tarooki, a Uniting Venues site based in Robe.

The Southern Ocean at Teeluk, near Kingston SE

The following day, Thursday 7 November, we spent the day at a number of Indigenous sites just north of Kingston SE, joined again by David New.

The first of these was Teeluk, a tradition Aboriginal site run by Meintangk man Doug Nichols, sharing his account of traditional Aboriginal life in the South East, sharing knowledge on hunting, gathering, tool making, and engaging in music and ceremony. Following an introduction at a freestanding shelter, we made our towards the beach through the dunes. Some of us took less-beaten paths, and came across a pair of antlers, these were likely from escaped deer from nearby game reserves. Arriving at the beach brought us face to face with the Southern Ocean, as well as the various detritus strewn around the shore, much of it tackle and plastic. Upon returning to the shelter, we had lunch, after which Doug shared further knowledge of the local Indigenous seasons, fire-making practices and throwing a boomerang (my first experience seeing in action).

That afternoon, we then travelled not too far to Sandy’s hut, another traditional site which now was home to Indigenous man Terry Hartman. Terry had spent much of his life working around regional Australia in mining towns, recently returning to the Coorong. With torrential rain descending upon us, Terry and David calmly took us on a tour of the site, noting sites of revegetation (amongst them, a long row of melaleuca howling in the wind) and a nearby swamp. The swamp was a significant site for cultural practice, and 50 years prior had succumbed to the effects of drainage elsewhere in the Limestone Coast. 2015 saw the first flows into the swamp since that time, with it bringing the first black swan in that time, an important totem. These results of this denote the dialogue between local Indigenous people (through the South East Aboriginal Focus Group) and the South East Natural Resources Management Board as an significant one, with mutual advocacy for one another (many other initiatives and outcomes seen here).

Our last day on the Coorong, Friday 8 November, took us to Tilley Swamp Conservation Park, a 1,525-hectare swamp area located 40 km south of Salt Creek. Much of Tilley Swamp is held in trust by Wetlands and Wildlife, a public company instigated by Tom Brinkworth and family with a focus on conservation and land management.

It bears noting that Brinkworth is not without controversy. One of the largest landholders in Australia (over 1 million hectares), the positive work of Wetlands and Wildlife is complicated by Brinkworth seven-time conviction of illegal land clearing, and introduction of deer in the region for hunting purposes (perhaps the source of the antlers we found the previous day).

1) & 2) Sections of the South Eastern Flows Drain System in Tilley Swamp

3) Conversation at Lunch

4) An old, knotted gum amongst teatree at Tilley Swamp

A tour with members of Wetlands and Wildlife, amongst them former CEO of the Drainage Board Evan Pettingill, took us along sections of the newly completed South Eastern Flows Drain, which feeds water into the Morella Basin for release into the Coorong’s Southern Lagoon when required in times of drought. As we continued through the Park, we came across many forms of native flora and fauna, include remnant mallee, old gnarled-red gums, multiple eagle nests, dozens of sleepy lizards, kangaroos and wallabies, and hundreds of black swans in the Morella Basin.

1) Morella Basin, harbouring hundreds of black swans

2) The discharge drain in the Coorong's South Lagoon

3) Looking north into the South Lagoon

A more challenging expedition of the day took us to the Baker’s Range drains made in the early 2000s to divert water from behind Bakers Range to Morella Swamp. The canyon-like cuttings extend some 17kms, a visible scar on the landscape from Google Earth (36°08'53.7"S 139°46'47.6"E). Needless to say, many of us were astounded at the immensity (and audacity) of the work.

1) A small section of the Baker's Range drains

2) Driving in the canyon-like drain

After departing Tilley Swamp, we spent a little time at the discharge point from Morella Basin to the Coorong’s South Lagoon, the first time visiting the area for many.

Our final day on the road, Saturday 9 November, centred on an audience with international artist and local landowner James Darling, who grew up in Melbourne but had lived in the South East for the past 40 years, seeing many changes.

James’ oration began with a reading from his journal (currently being edited towards a new book), with observations from 11 March and 24 May 2007, the height of the Millenium drought and impacts on the local environment. This prelude shifted into a discussion of his work, much of it employing mallee roots found in the region to encapsulate specific environmental phenomena or systems. As James noted, mallee landscapes are amongst the most degraded in the country, the result of European colonial settlers not understanding the role and function of plants in these environments.

Much of the discussion thereafter focussed on his and partner Lesley Forwood’s current exhibition, Living Rocks - A Fragment of the Universe, as part of the Venice Biennale at the 15th-century salt warehouse Magazzino del Sale, in collaboration with the Art Gallery of South Australia, the Australian String Quartet and JumpGate-VR. Though with challenges in getting the work to Venice, James indicated that the work’s exhibition in the Biennale had been a success, with between 300-700 people a day visiting the work.

Living Rocks used mallee roots to represent thrombolites, unique organisms that appear like rocks, but rather are accretions of microbes that emit oxygen when removed from water. Growing one cubic millimetre every 100 years, their ancestors were the only life forms for 3 billion years, creating the conditions for more complex life forms (through the Great Oxidisation Event). In the Limestone Coast, thrombolites are located at Lake Hordon South near Robe and Beachport, now a highly secretive and protected area.

In describing the work and its impacts, there was a keen sense of poetry on James’ mind, describing the intention of the work to bring understandings of Australia’s unique environments to the world, representing images of 3 billion years ago to the present day. Through the memory of our origin, he explained, lies a prophecy of the future: the vulnerability of the world, and the inevitability that microbes will inherit the world again. With this work was also his recognition of having only so many years left and the need to “confront limits of public ambitions and direct energies elsewhere”, such as writing and farm work - in effect, the end of his visual arts career.

The final day of the Land Arts Retreat, Sunday 10 November, saw us return to Mt Gambier. In the morning, we visited Ningarna Springs, a regenerated wetland area near Pt MacDonnell owned by Lyn Jones, who hosted our group for breakfast and took us a tour of the site. Lyn had spent many years removing exotic flora (especially blackberry bramble) and planting native vegetation, as well as introducing weirs at drains in the old dairy site to retain water in the landscape.

Scenes from our Ningarna Springs tour with Lyn

In the afternoon, we returned to the Riddoch Gallery for a public forum on the Retreat, accompanied by many of the people we had spent time with, including Aunty Michelle, David New, Mark Bachmann and Bob Delgano. Here, we spoke about our experiences of the retreat, as well as the complex and interrelated sociocultural, agricultural, hydrological, ecological and spiritual issues that the Retreat had drawn our attention to.

The Land Arts Retreat community forum at the Riddoch Gallery

Although we would soon part ways, many of us artists had begun conversations towards our responses to the region and the Retreat, as well as prospects of collaboration. For myself, I’m particularly interested in investigating the possibilities of cymatics in water-quality evaluation, as well as the employment of live-data streams towards real-time apprehension evaluation of the drainage system and regional environment.

In the final post, I’ll write about my reflections on both the Sir Robert Helpmann Theatre Residency and Land Arts Retreat.

The Sir Robert Helpmann Theatre Residency and Land Arts Retreat are made possible thanks to the following organisations: